Shell script bonus: while loops, arrays and more

Week 4 - shell scripts - Part III (optional self-study material)

1 While loops

In bash, while loops are mostly useful in combination with the read command, to loop over each line in a file. If you use while loops, you’ll very rarely need Bash arrays (next section), and conversely, if you like to use arrays, you may not need while loops much.

while loops will run as long as a condition is true and this condition can include constructs such as read -r which will read input line-by-line, and be true as long as there is a line left to be read from the file. In the example below, while read -r will be true as long as lines are being read from a file fastq_files.txt — and in each iteration of the loop, the variable $fastq_file contains one line from the file:

# [ Don't run this - hypothetical example]

cat fastq_files.txtseq/zmaysA_R1.fastq

seq/zmaysA_R2.fastq

seq/zmaysB_R1.fastq# [ Don't run this - hypothetical example]

cat fastq_files.txt | while read -r fastq_file; do

echo "Processing file: $fastq_file"

# More processing...

doneProcessing file: seq/zmaysA_R1.fastq

Processing file: seq/zmaysA_R2.fastq

Processing file: seq/zmaysB_R1.fastqA more elegant but perhaps confusing syntax variant used input redirection instead of cat-ing the file:

# [ Don't run this - hypothetical example]

while read -r fastq_file; do

echo "Processing file: $fastq_file"

# More processing...

done < fastq_files.txtProcessing file: seq/zmaysA_R1.fastq

Processing file: seq/zmaysA_R2.fastq

Processing file: seq/zmaysB_R1.fastqWe can also process each line of the file inside the while loop, like when we need to select a specific column:

# [ Don't run this - hypothetical example]

head -n 2 samples.txtzmaysA R1 seq/zmaysA_R1.fastq

zmaysA R2 seq/zmaysA_R2.fastq# [ Don't run this - hypothetical example]

while read -r my_line; do

echo "Have read line: $my_line"

fastq_file=$(echo "$my_line" | cut -f 3)

echo "Processing file: $fastq_file"

# More processing...

done < samples.txtHave read line: zmaysA R1 seq/zmaysA_R1.fastq

Processing file: seq/zmaysA_R1.fastq

Have read line: zmaysA R2 seq/zmaysA_R2.fastq

Processing file: seq/zmaysA_R2.fastqAlternatively, you can operate on file contents before inputting it into the loop:

# [ Don't run this - hypothetical example]

while read -r fastq_file; do

echo "Processing file: $fastq_file"

# More processing...

done < <(cut -f 3 samples.txt)Finally, you can extract columns directly as follows:

# [ Don't run this - hypothetical example]

while read -r sample_name readpair_member fastq_file; do

echo "Processing file: $fastq_file"

# More processing...

done < samples.txtProcessing file: seq/zmaysA_R1.fastq

Processing file: seq/zmaysA_R2.fastq

Processing file: seq/zmaysB_R1.fastq2 Arrays

Bash “arrays” are basically lists of items, such as a list of file names or samples IDs. If you’re familiar with R, they are like R vectors1.

Arrays are mainly used with for loops: you create an array and then loop over the individual items in the array. This usage represents an alternative to looping over files with a glob. Looping over files with a glob is generally easier and preferable, but sometimes this is not the case; or you are looping e.g. over samples and not files.

Creating arrays

You can create an array “manually” by typing a space-delimited list of items between parentheses:

# The array will contain 3 items: 'zmaysA', 'zmaysB', and 'zmaysC'

sample_names=(zmaysA zmaysB zmaysC)More commonly, you would populate an array from a file, in which case you also need command substitution:

Simply reading in an array from a file with

catwill only work if the file simply contains a list of items:sample_files=($(cat fastq_files.txt))For tabular files, you can include e.g. a

cutcommand to extract the focal column:sample_files=($(cut -f 3 samples.txt))

mapfile command

TODO

Accessing arrays

First off, it is useful to realize that arrays are closely related to regular variables, and to recall that the “full” notation to refer to a variable includes curly braces: ${myvar}. When referencing arrays, the curly braces are always needed.

Using

[@], we can access all elements in the array (and arrays are best quoted, like regular variables):echo "${sample_names[@]}"zmaysA zmaysB zmaysCWe can also use the

[@]notation to loop over the elements in an array:for sample_name in "${sample_names[@]}"; do echo "Processing sample: $sample_name" doneProcessing sample: zmaysA Processing sample: zmaysB Processing sample: zmaysC

Extract specific elements (note: Bash arrays are 0-indexed!):

# Extract the first item echo ${sample_names[0]}zmaysA# Extract the third item echo ${sample_names[2]}zmaysCCount the number of elements in the array:

echo ${#sample_names[@]}3

Arrays and filenames with spaces

The file files.txt contains a short list of file names, the last of which has a space in it:

cat files.txtfile_A

file_B

file_C

file DWhat will happen if we read this list into an array, and then loop over the array?

# Populate an array with the list of files from 'files.txt'

all_files=($(cat files.txt))

# Loop over the array:

for file in "${all_files[@]}"; do

echo "Current file: $file"

doneCurrent file: file_A

Current file: file_B

Current file: file_C

Current file: file

Current file: DUh-oh! The file name with the space in it was split into two items! And note that we did quote the array in "${all_files[@]}", so clearly, this doesn’t solve that problem.

For this reason, it’s best not to use arrays to loop over filenames with spaces (though there are workarounds). Direct globbing and while loops with the read function (while read ..., see below) are easier choices for problematic file names.

Also, this example once again demonstrates you should not have spaces in your file names!

Exercise: Bash arrays

- Create an array with the first three file names (lines) listed in

samples.txt. - Loop over the contents of the array with a

forloop.

Inside the loop, create (touch) the file listed in the current array element. - Check whether you created your files.

Solutions

- Create an array with the first three file names (lines) listed in

samples.txt.

good_files=($(head -n 3 files.txt))Loop over the contents of the array with a

forloop.

Inside the loop, create (touch) the file listed in the current array element.for good_file in "${good_files[@]}"; do touch "$good_file" doneCheck whether you created your files.

lsfile_A file_B file_C

3 Miscellaneous

3.1 More on the && and || operators

Above, we saw that we can combine tests in if statements with && and ||. But these shell operators can be used to chain commands together in a more general way, as shown below.

Only if the first command succeeds, also run the second:

# Move into the data dir and if that succeeds, then list the files there: cd data && ls data# Stage all changes => commit them => push the commit to remote: git add --all && git commit -m "Add README" && git pushOnly if the first command fails, also run the second:

# Exit the script if you can't change into the output dir: cd "$outdir" || exit 1# Only create the directory if it doesn't already exist: [[ -d "$outdir" ]] || mkdir "$outdir"

3.2 Parameter expansion to provide default values

In scripts, it may be useful to have optional arguments that have a default value if they are not specified on the command line. You can use the following “parameter expansion” syntax for this.

Assign the value of

$1tonumber_of_linesunless$1doesn’t exist: in that case, set it to a default value of10:number_of_lines=${1:-10}Set

trueas the default value for$3:remove_unpaired=${3:-true}

As a more worked out example, say that your script takes an input dir and an output dir as arguments. But if the output dir is not specified, you want it to be the same as the input dir. You can do that like so:

input_dir=$1

output_dir=${2:-$input_dir}Now you can call the script with or without the second argument, the output dir:

# Call the script with 2 args: input and output dir

sort_bam.sh results/bam results/bam# Call the script with 1 arg: input dir (which will then also be the output dir)

sort_bam.sh results/bam3.3 Standard output and standard error

As you’ve seen, when commands run into errors, they will print error messages. Error messages are not part of “standard out”, but represent a separate output stream: “standard error”.

We can see this when we try to list a non-existing directory and try to redirect the output of the ls command to a file:

ls -lhr solutions/ > solution_files.txt ls: cannot access solutions.txt: No such file or directoryEvidently, the error was printed to screen rather than redirected to the output file. This is because > only redirects standard out, and not standard error. Was anything at all printed to the file?

cat solution_files.txt# We just get our prompt back - the file is emptyNo, because there were no files to list, only an error to report.

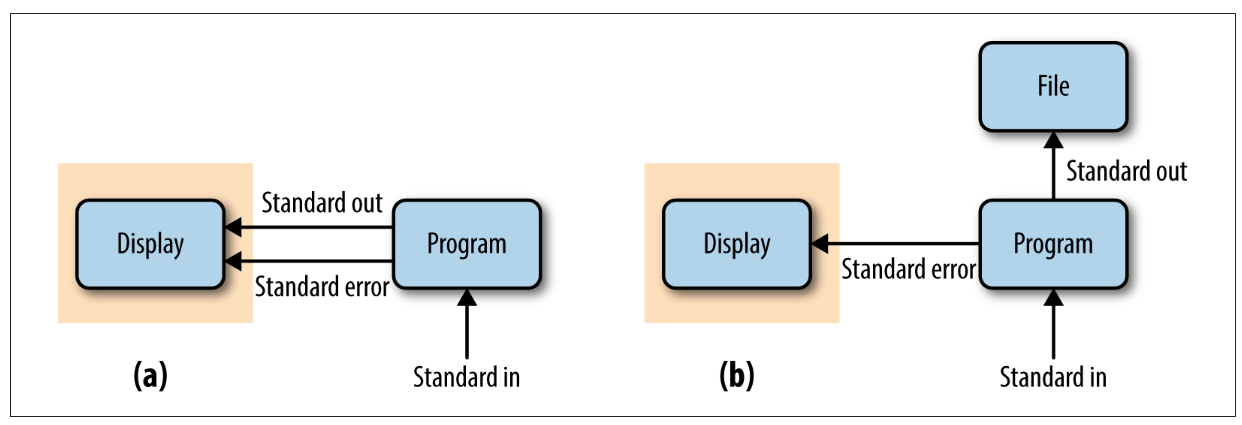

The figure below draws the in- and output streams without redirection (a) versus with > redirection (b):

To redirect the standard error, use 2> 2:

ls -lhr solutions/ > solution_files.txt 2> errors.txtTo combine standard out and standard error, use &>:

# (&> is a bash shortcut for 2>&1)

ls -lhr solutions/ &> out.txtcat out.txtls: cannot access solutions.txt: No such file or directoryFinally, if you want to “manually” designate an echo statement to represent standard error instead of standard out in a script, use >&2:

echo "Error: Invalid line number" >&2

echo "Number should be >0 and <= the file's nr. of lines" >&2

echo "File contains $(wc -l < $2) lines; you provided $1." >&2

exit 1